|

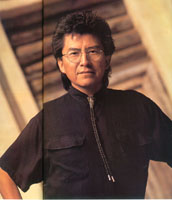

Jeweler

orbits the outer limits

by

Emily Drabanski

Similar

to shaping his straight-edged, yet elegantly balanced geometric

jewelry designs that defy categorization, L. Eugene Nelson enjoys

working on the cutting edge of the contemporary art world. Similar

to shaping his straight-edged, yet elegantly balanced geometric

jewelry designs that defy categorization, L. Eugene Nelson enjoys

working on the cutting edge of the contemporary art world.

His finely crafted pieces, which sport such titles as the Star Wars,

Melt-Down and Structured Space series, continue to garner recognition

from museums and collectors --many who first discovered his work

at the Santa Fé Indian Market. His jewelry features silver

and gold work that he designs, constructs and shapes often punctuated

by fine pieces of turquoise, lapis and coral.

Nelson, who only began to grant interviews this past year, speaks

with eloquence and conviction about his art during an interview

at his home in Alburquerque. The home is simple, yet carefully appointed

with beautiful paintings and pottery by Native Americans. Two large,

contemporary family portraits show Eugene along with his wife, Vickie,

and three daughters, Nicole, 14; Joselyn, 10; and Alissa, 6.

Nelson, who styles his jet black hair in a contemporary cut, is

the first to acknowledge his Navajo heritage. But he'd like people

to take him seriously as a contemporary artist, who happens to be

Native American.

"I'm the first to admit that being Native American has helped me

in the art world," Nelson says. He says shows such as the Santa

Fé Indian Market, Eight Northern Indian Pueblos Arts and

Crafts Show and the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair and Market gave

him the vital contacts he has in the art world today. These shows

still are important to him, but he says more than winning prizes

he enjoys his contact with his customers and their feedback.

"I just say that I'm an artist. I don't even say that I'm a silversmith

or goldsmith. I don't have that type of technical education or training,"

Nelson says modestly of his work, which exhibits an extraordinary

amount of precision and detail.

The 42-year-old artist credits much of his commitment to detail

and precision to the work he did in his mechanical drawing classes

from the seventh grade through high school and architecture classes

in high school.

In high school, Nelson excelled in cross-country distance running

and track. He lettered in both sports and was named to the all-state

teams. This coupled with his excellence in academics led to offers

for college scholarships.

"I was at an age when I said I'd just like to do my own thing for

awhile and see what happens. So I didn't go to college then," Nelson

says.

In the fall of 1973, he took a mechanical drawing class at the Southwest

Indian Polytechnic Institute, but felt unchallenged repeating techniques

he'd already mastered in his younger years.

"In the summer of 1974, a friend since grade school and a fellow

West Mesa High School graduate, Charlie Platero Jr., a Navajo from

the Caņoncito Navajo Reservation, introduced me to the basic skills

of silversmithing. As far as I can recall, Charlie's dad had been

one of the few silversmiths on the reservation prior to the big

Indian jewelry boom of the '70s."

"The instructions were brief and may have lasted only a week, but

watching Charlie and his dad work the metal with many of their own

handmade tools impressed me. I was also impressed to see such talent

and skill passed from father to son. This was my only experience

and connection with the aspects of traditional Navajo jewelry making

and although brief, I feel privileged and blessed for the experience.

"Basically, what I had learned then is what I utilize today in my

work," Nelson says. First, he says, was not to be afraid to "put

the heat" to the metal (useful in controlling solder for clean connections

and keeping defined details such as lines and edges). Second, he

notes, was "to work" the metal by bending, twisting and shaping

using the least number of tools (sometimes making his own) to ensure

the development of his own style.

In 1975, he was offered a scholarship to the University of New Mexico

and continued his studies, mostly geared toward engineering. He

continued to dabble with jewelry making, while perfecting his soldering

techniques.

"In 1980, I came across an article about Native American contemporary

artists. And the work of a Hopi jeweler, Charles Loloma, impressed

me the most because of his blending traditional design and mostly

Southwest materials with a bold, contemporary style that was uniquely

his own. This was exciting to me to see something other than the

usual and marketable designs of the traditional 'Indian jewelry

scene.' This was my first clue that the 'Indian jewelry craft world'

was changing to an 'Indian art world.'"

Viewing Loloma's work inspired Nelson to design his own pieces.

"I wasn't interested in creating or copying work that was like his,

but I liked the idea of creating work that was uniquely my own."

Today, Nelson often speaks to young artists and encourages them

not copy him, but to find their own style and run with it.

"The challenge is to create designs that no one else has thought

to make. However, when you do become successful with your designs,

then the challenge is to continue to be creative and not to be satisfied

with your past successes.

Success did not come overnight for Nelson. In 1977 he left college

to work in production at KOBTV (NBC) in Alburquerque. In 1980, after

he got married, he went to KOATTV (ABC), where he eventually became

supervisor of the editing department. "This type of work suited

my personality. I had to deal with seconds and half-seconds in timing.

It was quite comfortable for me because I'd always been interested

in math, precision and detail."

What he didn't like about the work was that it kept him away from

his family, as well as his growing interest in art. His shifts often

kept him at the station until 2 a.m., while his wife was leaving

for work a few hours later.

"In 1982, Irealized that I was really enjoying working on my art.

I started to do more Indian art shows and was getting a good response.

I still hadn't envisioned that I could make a living as an artist,

but I knew I loved the work."

"It was at the same time I was following my faith and growing spiritually

and I knew I did not want my children to be growing up without a

father. I felt the Lord was starting to help me get ready for my

new life."

Even though his work drew a good response, he decided not to just

produce work designed to sell. "I really wanted to create my own

work." And he found his original designs attracted a growing market.

His wife, Vickie, who is Hispana, encouraged him to become a professional

artist, especially because it allowed him to be more involved with

the family. She is a program manager at the Latin American Institute

of the University of New Mexico.

Until that point he realized he had not been confident about making

his living as an artist. Although, he says, when he reflects on

his family's history, he sees a long association with the arts.

His grandparents and extended family members, for instance, were

weavers and potters. "My grandmother on my mother's side really

influenced me. When I was young I spent most of my summers on the

reservation at my grandmother's house. And she was a weaver."

Similar to many Native Americans, he struggled to find his place

in two worlds. Until he was 7, he lived in Ogden, Utah, where his

father worked for the government.

"I grew up with kids that were Hispanic, black and Anglo. We all

'just played together. I was growing up in the '50s and we all loved

Westerns. And I know this sounds wild, but when we played 'cowboys

and Indians' my brothers and I usually wanted to be the cowboys!"

He says he actually dealt with major culture shock when the family

moved back to Shiprock. As a youngster, he felt isolated because

he didn't know how to speak Navajo and struggled to be accepted

by other Navajos.

While he values his heritage and still visits family on the reservation,

he's comfortable living in Alburquerque. "I'm a people person and

the reservation is wonderful, but it can get awful lonely out there,"

Nelson says with his characteristic grin.

His father, Tom D. Nelson, who raised 10 children along with his

mother Virginia, became a Southern Baptist missionary not long after

their move back to New Mexico. They continue as missionaries in

Arizona.

He says his father's "leap of faith" from the security of a

government job into the ministry has had a profound effect on his

life.

One reason he also chooses to live in Alburquerque is because he

and his family are active members of the Del Norte Baptist Church.

"My art is important to me, but it's just a part of my life. My

faith and family will always come first," Nelson emphasizes.

He respects other Indians who observe traditional Native American

beliefs and asks for the same respect for his beliefs.

"So many Native American artists are trying to sell their art by

telling the customers about some type of Native American spiritual

belief. Some of those people hold those beliefs, but there are others

who are doing it just to make a sale," he insists.

"I ask young people to know what their beliefs are and to be able

to talk about them honestly." He chooses not to use any religious

symbols in his own work and is straightforward about his philosophies

with his customers.

He cautions against the heavy commercial influences that appear

in some artists' work. While the feather once meant something special,

he's afraid it's become a more commercial symbol like the ubiquitous

howling coyote that once filled many Santa Fé shops.

So he continues to sketch out his original designs in pencil on

his graph paper in his small studio. The play of light and shadows

on city buildings, the way the light filters through the living

room blinds, all influence Nelson in his playful designs that often

seem part of a science fiction fantasy. He enjoys science fiction

films that examine man's struggles with technology, such as Blade

Runner.

"Being a self-taught jeweler/artist, and not having any of the major

outside influences that usually occur through formal training or

family trade involvement, has allowed me not to feel any obligations

or boundaries in designing my work. However, living in the Southwest

I cannot help but be influenced by the creativity of others.

"My approach is not simply to make jewelry, but to create art. Enjoyment

and creativity are both necessary in this process. In designing,

I approach my artwork as a three-dimensional object with details

that only complement the overall piece. This allows me to highlight

certain parts of the work without overdoing the piece and ending

up with an ornate, and sometimes, gaudy appearance."

Today, he still works in a small converted utility room using many

of the same tools from years ago. "Perhaps, because I had such simple

tools it forced me to be more creative and precise in my work."

His thrifty nature has encouraged him to keep a drawer full of tiny

scraps of silver. These scraps become integral parts of his Melt

Down series and other constructed pieces. All of his work has a

strong three-dimensional quality and some pieces actually have different

designs on the front and back, so they can be worn in reverse. Others

feature delicate silver dangles because he likes to create a kinetic

effect when a piece is worn.

Nelson calls the Wheelwright Museum one of his strongest supporters.

"Some galleries have a tendency to look at your work and try to

control what you create. But I've been blessed because I've been

told to go and do my own thing." Nelson also shows at Wright's Collection

of Indian Arts and Southwest Contemporary Jewelry in Alburquerque,

as well as the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff. He's also

participated in shows at the Heard Museum and Museum of Northern

Arizona, as well as the Institute for American Indian Arts in Santa

Fé. He'll be back at Santa Fé Indian Market, August

23-24, sharing a booth with his brother Bennie Nelson, who paints

under the name Yellowman. "My brother and I have a little bit of

competition going," he says. "But I have to give him credit. He

always said he'd be an artist from the time he was in the second

grade. I was pretty cynical about it when he was serious about art

in high school. But we're both now working as artists." Another

generation seems headed in the same direction. Bennie's son, Ben

Nelson, made the news last year when he presented President Clinton

with a painting. Eugene says his daughters are starting to show

an interest in art, as well as writing.

"I just continue to encourage them to explore and find out

what they like about art," he says.

What lies ahead for Eugene? "My attitude has always been that my

last piece has to be my best piece. But I'm constantly challenging

myself. I'd really like to try my hand at sculpture next."

|